Math 153 diary, fall 2009: second section

Later material

Previous material

In reverse order: the most recent material is first.

| Tuesday, November

10 | (Lecture

#20) |

|---|

L'Hôp

L'Hôpital's (also L'Hopital's

or L'Hospital's) Rule is a method

of evaluating certain very special limits. It is worth showing to you

because it is another neat application of "local linearization", and

some really important limits become easy to evaluate. However, it must

be used with some care. One quote I found on the Internet declared,

"Giving l'Hopital's Rule to a calculus student is like handing a

chainsaw to a three year old."

Mr. Nakamura discussed a version of L'H with you:

L'Hôpital's Rule (version 1, for 0/0)

Suppose that f and g have continuous derivatives, and that

f(a)=g(a)=0 (the eligibility criterion). If

limx→af´(x)/g´(x) exists, then

limx→af(x)/g(x) exists and is the same value.

Comment 1 It is very important to check the eligibility

criteria. For example, if you try to compute

limx→2x2/(5x+7) by instead computing

limx→22x/5 you will report the false answer 4/5

instead of the correct answer 4/17.

Comment 2 L'H is so appealing maybe because it looks like what

we all believe the Quotient Rule should be. It is a version of

paradise, maybe. (More theology is below, so please just wait.)

That's why people want to use it, even when they shouldn't.

The L'H above is called the 0/0 ("zero over zero") form. There are

other forms. For example, one version is very useful in certain

practical applications.

L'Hôpital's Rule (version 2, for ∞/∞)

Suppose that f and g have continuous derivatives, and that

f(a)=g(a)=∞ (the eligibility criterion). If

limx→af´(x)/g´(x) exists, then

limx→af(x)/g(x) exists and is the same value.

scale, then one might consider that x could be in nanoseconds, so

large values of x could be more relevant than one might initially

suspect.

One way to compare these functions is to consider their ratio and see

what happens when x gets large. So we looked at

limx→∞x10,000/e.001x. Of

course people said that the top→∞and the bottom→∞

separately. So this is eligible for L'H. The result, after

separate differentiation of the top and bottom is

limx→∞[10,000x9,999]/[.001e.001x]. Is

this any improvement? A completely naive person might not see much

improvement, but again this is eligible for L'H since the top

and bottom both→∞. So the separate differentiations, done

carefully, give

limx→∞[10,000·9,999x9,998]/[(.001)2e.001x]. Now I hoped that people would see a pattern.

(L'H)10,000

We can compute

limx→∞x10,000/e.001x by

applying L'H ten thousand times in succession. I hope that you can see

the result, almost. After 10,000 separate differentiations of the top and bottom we need to evaluate

limx→∞(10,000!)/[(.001)10,000e.001x]

Here by 10,000! I mean the product of the integers 10,000 and 9,999

and 9,998 and 9,997 and ... all the way down to 1. This is called a

factorial and you will see many factorials in Math 152. Actually, for the purposes of this computation I don't care much about specific constants, and really I think of the limit as

limx→∞CONSTANT1/[CONSTANT2e.001x]

because then it is clear that the exponential, which is really growing

and growing and growing will make the limit equal to 0.

The final result

So, in fact, eventually e.001x grows faster than

x10,000.

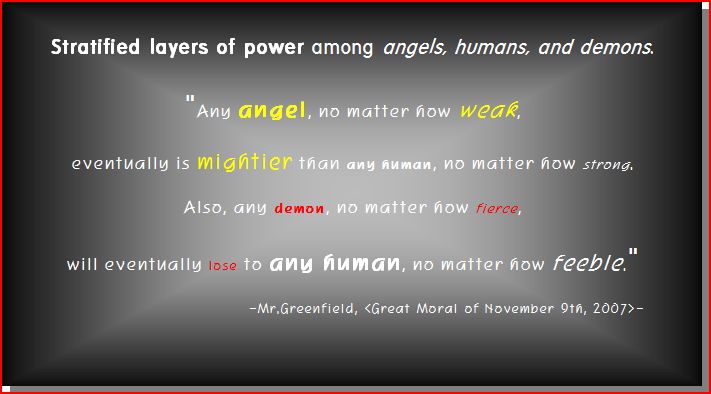

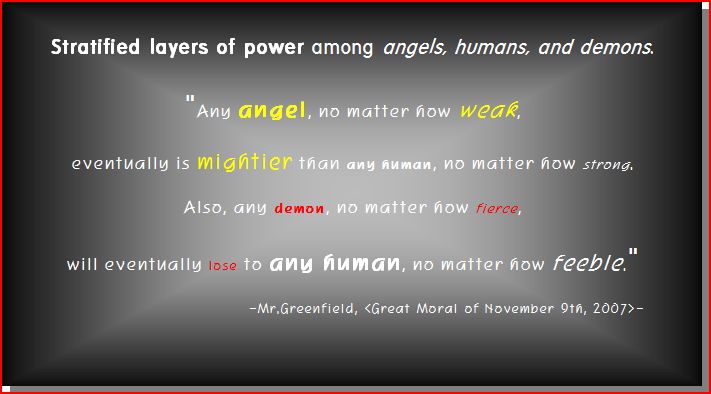

Angels and humans

We could think of functions with exponential growth, so eAx

with A>0, as angels, and functions with power of x growth,

xA with A>0, as humans. (If A happens to be an integer

we get a monomial, and sums [families?] would be polynomials.) So if

you think about it, eventually any angel is stronger than even the

most powerful human.

Another not so obvious use of L'H

Here was another pair of functions we considered.

Formulas for

the functions | Value when x=5 | If 1 unit is an inch,

then ... |

| (ln(x))300 | 1.005·1062 | This is

only about 1.7·1044 times the

theoretical

diameter of the universe! |

|---|

| x1/3 | 1.7099... | Almost two inches! |

|---|

We use L'H to compare the rates of growth. So look at

limx→∞[(ln(x))300]/x1/3. You need to really

believe in (?) logs and powers of x, but, if you do, you should see

that the top and bottom both →∞separately. So apply L'H by

computing derivatives, and this limit results:

limx→∞[300(ln(x))299(1/x)]/[(1/3)x–2/3]. This

computation seems more intricate to me than the earlier one. The Chain

Rule is needed. The result is a compound fraction, and here it is

worthwhile to simplify the compound fraction. The (1/x) makes an

additional power of x appear "downstairs" and we get (after we

recognize that 1+(–2/3)=1/3 !)

limx→∞[300(ln(x))299]/[(1/3)x1/3]. Again L'H

applies (yes, we check the eligibility!) and the result is

limx→∞[300·299(ln(x))298](1/x)/[(1/3)2x–2/3].

Look! 1/x is on top, which changes the power on the bottom from

x–2/3 to x1/3. The structure of the computation

should be observed.

(L'H)300

We can compute limx→∞[(ln(x))300]/x1/3 by using L'H three

hundred times in a row, each time carefully (!) checking (!!) the

resulting quotient for the eligibility (!!!) of the top and bottom. Ha. The result will be

limx→∞(300!)/[(1/3)300x1/3]

and this easily has limit equal to 0. Maybe it is amusing to notice we

can get the exact values of certain constants, but for the final

result of this computation, the exact values of the constants don't

matter.

The final result

So, in fact, eventually x1/3 grows faster than

(ln(x))300.

And now demons ...

Well, if humans are postive powers of x, then maybe demons could be

any powers, no matter how large, of logs. So one feeble human might be

x.000005 and one ferocious demon might be (ln(x))600,000. Eventually even the most feeble

human will overpower the most terribly ferocious demon.

Moral (?) lessons concerning this hierarchy

A former student, Mr. Harrison, gave me, almost casually,

the lovely definition of hierarchy as "stratified layers of power". It

is certainly appropriate. Anyway, below is an effort by another former

student, Mr. Park

to note my comments, and to

the right is a picture. I like pictures. |

|

This ends discussion of material eligible for the

second

exam which will be given one week from this lecture.

Go to the third diary file for the last half of this lecture.

| Thursday, November

5 | (Lecture

#19) |

|---|

I'll repeat and complete the story I ended with last time.

Another story

A line

segment joins the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the first quadrant. A

rectangle in the first quadrant with sides on the x- and y-axes sits

inside the resulting triangle, and has a vertex on the line

segment. What is the largest area that such a rectangle can

have?

Comment

Wel, darn it, I tried to write the specifications very

carefully. After class, Mr. Orrico and

Ms. O'Sullivan convinced me that my

paragraph was not carefully written enough. I think they were

correct. Instead of the phrase "sits inside the resulting triangle,

and has a vertex on the line segment", I had written "[has] a vertex

on the line segment". In that case (future lawyers should follow this

carefully!) a rectangle with vertices at (0,0), (3,0), (3,2), and

(0,2), that is a rectangle with the line segment as a diagonal will

have all the other eligible rectangles inside it. So it would

definitely be the largest. This isn't what I wanted. So my

specification was not written precisely enough. Let me go on with the

changed specification written above.

Probably the first thing I would do when meeting a problem of this

type is to draw a picture. I think my sketch would look something like

what's to the right. Certainly, I would need the line segment joining the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the

first quadrant which is drawn. Then I likely would try to draw

a typical rectangle. Although I tried to write the specification of

the rectangle in a direct way, my desire to be brief may have made

this difficult to understand. The rectangle has sides on the x- and y-axes as shown. It

also has a vertex on the line

segment. Legitimate questions include, "What's a vertex?" and

"What line segment?" I hope, even if you've not heard the word before

or this use of the word, that you would know "vertex" means a corner

of the rectangle. And the first sentence of the problem defines "the

line segment".

Probably the first thing I would do when meeting a problem of this

type is to draw a picture. I think my sketch would look something like

what's to the right. Certainly, I would need the line segment joining the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the

first quadrant which is drawn. Then I likely would try to draw

a typical rectangle. Although I tried to write the specification of

the rectangle in a direct way, my desire to be brief may have made

this difficult to understand. The rectangle has sides on the x- and y-axes as shown. It

also has a vertex on the line

segment. Legitimate questions include, "What's a vertex?" and

"What line segment?" I hope, even if you've not heard the word before

or this use of the word, that you would know "vertex" means a corner

of the rectangle. And the first sentence of the problem defines "the

line segment".

Almost surely in my mind I would play around with the problem as

pictured, and try to see some of the eligible rectangles. The pictures

I would look at would include the two below. If the vertex were very

near (0,2), as in the left picture, I see that one side of the

rectangle would be almost 2 units long, while the other is very

small. The area of that rectangle would be small. On the other hand

(right picture), if the vertex were very near (3,0), one side of the

rectangle would be almost 3 units long, while the other is very

small. Again the area would be small. This encourages me to think

that, yes, there is a maximum and almost surely the max area will

occur for some rectangle with vertex "inside" the segment (at a

critical point of the algebraic model we will build).

| Two "extreme" rectangles |

|---|

Small area

|

Also small area

|

What to do ...

I mentioned in class that there is sort of a translation

process, going from the problem statement and creating a calculus

problem. I find this, even though I have a great deal of experience,

to be difficult. I generally need to read the problem statement very

carefully, and usually I need to read the statement several

times. Then there is an analysis step, where the calculus

problem is solved. This is usually more straightforward. It isn't

simple, because of course the opportunity for error is always present:

arithmetic errors, algebra errors, calculus errors. Certainly I have

made all of these, but somehow those can be fixed, at least for me,

more easily while the translation process definitely stubbornly proves

to be more difficult, at least for me.

Building the algebraic model

We will need the equation for the line segment. In class I tried to

describe how I would "guess" this equation. Since this is top secret

and also silly, I will just write it here: (x/3)+(y/2)=1. Well, o.k.,

my guessing method goes like this: the equation will involve both

variables since the line is neither vertical (x=const) nor horizontal

(y=const). Therefore it could be written

(x/something)+(y/something else)=1. Then plugging

in both (0,2) and (3,0) give me the values of something and

something else. What about the area of the rectangle? If

the coordinates of the point p are (x,y), then the area is xy.

I'm almost "there". The objective function is xy. The constraint

situation certainly involves (x/3)+(y/2)=1 but there is just a bit

more. Notice we are in the first quadrant, so that both x and y are

non-negative. Now my model follows:

Constraint(x/3)+(y/2)=1 and x≥0 and y≥0.

Objective Maximize xy.

As before I'll use the constraint to reduce the number of variables in

the objective. So (x/3)+(y/2)=1 becomes y=2[1–(x/3)] and xy becomes

2x(1–(x/3)). But don't forget the remainder of the constraint, which

becomes a domain restriction: x is in the interval [0,3].

The resulting calculus problem

Find the max value of f(x)=2x(1–(x/3)) when x is in the interval

[0,3]. We know that the maximum of f on [0,3] occurs either at

endpoints or critical points.

• Endpoint evaluation

f(0)=2·0(1–0)=0; f(3)=2·32(1–(3/3))=0. I bet

the max is inside, at a c.p.

• Critical point analysis Since

f(x)=2x(1–(x/3)) I know that

f´=2(1–(x/3))+2x(–1/3)=2–(4/3)x. Therefore the only c.p. is where

2–(4/3)x=0 so x must be 3/2. f(3/2)=2(3/2)(1–(1/2)) is positive, so

this is the maximum value. Yes, it "simplifies" to 3/2. The answer to

the problem is 3/2. Notice that the problem requests the largest area. We should attempt to answer

the question that is asked (so remarking that the dimensions of the

rectangle are ... and ... is not responsive!).

You should ...

Do 8 or 10 of these problems yourself, possibly together with other

students. Certainly what I wrote about is much more than I expect you

to write, but I would hope that, after sufficient experience,

you would think through such problems in much the same way as what's

above. I wanted to help you learn the process.

Practice is essential to your own ability to answer questions

of this type. The "translation" skill, that is, constructing the

correct mathematical model, is very important in applications.

A story about smallest

A line segment joins a point on the

positive x-axis with a point on the positive y-axis. The line segment

goes through the point (3,2) and creates, with the appropriate parts

of the x- and y-axes, a triangle. Find the smallest area of such a

triangle.

|

We discussed this a bit. We sketched the geometric situation

relatively quickly, but then students seem to have found making the

transition from the geometry to an algebraic description not so

easy. There's a diagram to the right. It shows a "typical" line

segment which joins a point on the

positive x-axis with a point on the positive y-axis and which

also goes through the point

(3,2).

|

|

As I wrote in a discussion of a previous geometric "story", I would

play around with the problem. When the point on the x-axis is very

close to (3,0), then the line would tilt "way up", very steeply. The

length of the line segment would be large and the area would be large

also (the length of the base →3 while the height →∞.

The area, which is (1/2)(base)(height) would therefore be large.

Similarly, if we were to pull the point on the x-axis far away from

(3,0), the slope would be close to 0, and the length of the line

segment would be large. The length of the base →∞ while the

height →∞. Again, the area would be large.

|  |

This seems to suggest that the area varies, and that "somewhere

in the middle" there is a minimum, and the minimum will occur at a

critical point. To the right is a very vague picture of x and A(x),

the area of the triangle when (x,0) is one end-point of the

segment. Here we note that the x's are in the interval (3,∞)

because otherwise we won't get a triangle -- the line segment won't

hit the positive y-axis. Also, I drew the graph so that as

x→3+ the area function gets very large, and a similar

behavior occurs as x→∞.

This seems to suggest that the area varies, and that "somewhere

in the middle" there is a minimum, and the minimum will occur at a

critical point. To the right is a very vague picture of x and A(x),

the area of the triangle when (x,0) is one end-point of the

segment. Here we note that the x's are in the interval (3,∞)

because otherwise we won't get a triangle -- the line segment won't

hit the positive y-axis. Also, I drew the graph so that as

x→3+ the area function gets very large, and a similar

behavior occurs as x→∞.

How about the transition from picture to an algebraic description? The

area is (1/2)xy, the Objective Function. How can we relate x and y

(the Constraint)?

If a diagram of the situation is labeled, then

some restrictions almost yell at the reader. Look to the right.

Certainly x>3 and y>2. And there are bunch (well, three) similar

triangles which give some further relationships between the

variables. For example, the big triangle and the lower right small

triangle tell me that y/x=2/(x-3), so that y=(2x)/(x-3). And therefore

the function we need to minimize is f(x)=(1/2)(x)(2x)/(x-3). What is

the domain of this function when used to describe this problem?

Certainly, x>3. There is no other restriction. Now we have turned

this into a calculus problem.

Certainly x>3 and y>2. And there are bunch (well, three) similar

triangles which give some further relationships between the

variables. For example, the big triangle and the lower right small

triangle tell me that y/x=2/(x-3), so that y=(2x)/(x-3). And therefore

the function we need to minimize is f(x)=(1/2)(x)(2x)/(x-3). What is

the domain of this function when used to describe this problem?

Certainly, x>3. There is no other restriction. Now we have turned

this into a calculus problem.

A calculus problem

What is the minimum of f(x)=x2/(x-3) for 3<x<∞?

(I canceled the 2's and combined the x's.)

• Endpoint evaluation There are no

endpoints! But I would still begin with some sort of analysis or

understanding of what happens out towards the edges. So maybe I should

call this

Edge analysis What happens as

x→∞? Well,

limx→∞f(x)=limx→∞sqrt(x2/(x-3)].

When x gets very large, we have a degree 2 polynomial on top and just

a degree 1 polynomial on the bottom. We analyzed such situations

before, and the result is that x→∞.

Now what happens as x→3+? Well,

x2→32. But 1/(x-3) is like 1/(something small and

positive), which is large and positive. So I bet that the product of

these two →∞, just as we should expect from our previous

thoughts.

Comment I like the idea of wearing both belt and suspenders to

keep my pants from falling down. Well, maybe not exactly that, but I

certainly do like the idea of reinforcing my geometric understanding

of the problem with another, algebraic approach. Both methods should

be used! Also, this way, I can be sure that if we identify

critical points, the resulting value(s) of the function will include

the minimum, and won't be a maximum. As I mentioned in class, there

have been some interesting real world failures of engineering projects

where this identification (max vs min) was neglected.

• Critical point analysis If

f(x)=x2/(x-3) then

f´(x)=[(2x)(x-3)-(1)x2]/(x-3)2 (Quotient

Rule). Then f´(x)=0 when the top is 0, so we need to solve

2x(x-3)-(1)x2=0. We can factor this (it is a toy

problem!) and get x[2(x-3)-x]=0 which has roots x=0 (first factor) and

x=6 (second factor). We can discard 0 since that is not in the domain

for this problem. Therefore the minimum area occurs when x=6 (we only

know this is a minimum because we did the edge analysis,

otherwise we'd need more work), and f(6)=36/3=12.

Resembles...?

The last two stories had pictures which resembled each other quite a

bit. We minimized an area, and we maximized an area. The two problems

are actually related to each other. They are examples of what are

called dual problems. In economics, such problems occur when we

want to maximize profit. This might be the same as minimizing cost. In

physics, the ideas are minimizing work and maximizing potential

energy.

My darling, struggling in the ocean!

The last story for class.

I am standing on a straight beach

and my darling is swimming in the ocean, a quarter mile from

shore. The closest point to my darling is two miles down the

beach. The sharks attack, and I must get to my darling as soon as

possible. I can run a mile in 10 minutes and swim a mile in 40

minutes. How can I get to my darling in the least time?

| As I mentioned in class, this is actually not such a toy

problem. Similar problems arise in optics frequently: minimizing

travel time when the speed of light in different materials

varies. I've attempted to sketch the situation, as seen from "above".

How can I get from my initial position to my darling? |  |

Pure strategy #1 Swim all the way!

Swim directly. The distance is sqrt((1/4)2+22),

about 2.01555 miles. At 40 minutes per mile, this takes about

80.6226 minutes. |

|

Pure strategy #2 Run as much as possible.

I run 2 miles down the beach, and then swim. So the 2 miles running

take me 20 minutes, and the 1/4 mile swimming takes 10 minutes. The

total time is 30 minutes. |

|

A "mixed" strategy? Run for a while, then swim.

It is not clear but maybe some blend of the two is faster. So I

could run part of the way, and then swim directly to my darling. |

|

|

Suppose

the "breakpoint" between these two activities is x miles from the

point on the beach which is closest to my darling. Then I'd run 2-x

miles, which would take 10(2-x) minutes. I would need to swim the

length of the hypotenuse of a triangle with legs x and 1/4 long:

that's sqrt(x2+(1/4)2) miles, and that would

take 40sqrt(x2+(1/4)2) minutes. The total time

would be f(x)=10(2-x)+40sqrt(x2+(1/4)2). The

domain of interest is [0,2]. |

Amazing!!!

Amazing!!!

To the right is a fairly careful graph of f(x) (which I requested as

the QotD). Notice that there is a critical point in the

interval [0,2]. The critical point is close to 0. I used my "friend"

Maple to find the critical point. Partly

this is because I am lazy, but it is more because I am tired. This

computation could be done by hand, because the most "difficult"

part of it is just solving a quadratic question. The first instruction

defines f as the algebraic mess we have above. Maple echos the definition so that I can check

it is what I want (I make lots of typing errors!). The second

instruction differentiates this formula. The third instruction, which uses

the word solve, sets the previous

expression (that is what % means) equal

to 0. The answer is exact and comes from the quadratic formula. Then I

substituted this into the expression for

f. Since I didn't "understand" the expression, I used evalf to find a 10 digit approximation to the

answer.

> f:=10*(2-x)+40*sqrt(x^2+(1/4)^2);

2 1/2

f := 20 - 10 x + 10 (16 x + 1)

> diff(f,x);

160 x

-10 + --------------

2 1/2

(16 x + 1)

> solve(%);

1/2

15

-----

60

> subs(x=%,f);

1/2 1/2 1/2

15 2 16 15

20 - ----- + -------------

6 3

> evalf(%);

29.68245837

At the all swimming endpoint, the time needed was about 80.6226

minutes. At the most running endpoint, the time needed was 30

minutes. The ideal strategy (at least for minizing time!) gets me to

my darling in less time than that: 29.6824 ... minutes.

I will certainly happily admit that this is not a great difference in

time. But you should see that there is a difference, and in

other problems the difference might be significant.

The speed of light in vacuum (air is about the same) is

299,792,458 meters per second (I copied this!). This speed is

frequently called c. "Denser media, such

as water and glass, can slow light much more, to fractions such as 3/4

and 2/3 of c." This difference is responsible for light "bending"

or refracting, because light travels (!) to minimize time.

|

L'Hôp

This is the next topic in the syllabus. L'Hôpital's (also

L'Hopital's or L'Hospital's) Rule is a method of evaluating certain

very special limits. It is worth showing to you because it is another

neat application of "local linearization", and some really important

limits become easy to evaluate. However, it must be used with some

care. One

quote I found on the Internet declared, "Giving l'Hopital's Rule

to a calculus student is like handing a chainsaw to a three year old."

The example I was going to begin with is

limx→0[sin(9x)/(e6x-1)]. "Plugging in" gets

no information, since we have 0/0. By the way, 0/0 limits can have

strange and varied behavior. For example, consider as x→0 the

three expressions x2/x and x/x and x/x2. They

all result in 0/0 when we just plug in. But if you think about them a

bit, the first has limit=0, the second has limit=1, and the limit for

the third expression does not exist. So 0/0 can conceal lots of

different behaviors.

You'll learn more about L'H on Monday.

| Tuesday, November

3 | (Lecture

#18) |

|---|

Exam warning!!!

The second in-class exam will be given Thursday, November 19, at the

usual class time and place. More information will be available

soon. Pleased study carefully.

Graphing a function

I gave data about a function in a rather strange way.

- f is a differentiable function whose domain is all real

numbers except for –2 and 1.

- f´ is positive only in the intervals x>3 and

–2<x<0.

- These limits are known:

limx→1–f(x)=–∞;

limx→1+f(x)=+∞;

limx→–2+f(x)=–∞;

limx→–2–f(x)=–∞;

limx→+∞f(x)=–1;

limx→–∞f(x)=0.

This is a great deal of mostly "qualitative" information (the

limits). I'm not giving any specific values of f, for example. I aimed

at drawing a qualitatively correct graph, but did admit that I

could "predict" how big f(3) was, for example.

Thinking about the graph of y=f(x)

The process is important. I'll try to go slowly through every bit of

information. I may make mistakes, and I may have to fix things

up. I'll only be able to sketch somethng which is qualitatively

correct.

|

Fact f is a differentiable function whose domain is all real

numbers except for –2 and 1.

Response I'd probably try to indicate somehow to myself that

the graph I'll draw should not appear when x=–2 and on x=1.

|

|

|

|

Fact f´ is positive only in the intervals x>3 and

–2<x<0.

Response f is increasing in those intervals where the

derivative is positive. An important word in the "Fact" sentence is

only. To me this says that f is increasing only in the

intervals from –2 to 0 and from 3 upwards. In interval notation, these

are (–2,0) and (3,∞). Probably f will be decreasing

in other intervals.

|

|

|

|

Fact limx→1–f(x)=–∞.

Response The symbols x→1– mean x is getting

close to 1 from the negative (left) side. And then –∞ means

that f(x) is getting large, but large negative, so the graph is going

down. What I would expect is something like what is shown here.

|

|

|

|

Fact limx→1+f(x)=+∞.

Response Here we have x→1+ and we should

consider x getting close to 1 from the right, positive side. The

+∞ means that f(x) will be getting very large positive. The

direction of approach and the largeness combine to get a sort of piece

of a graph which looks like what is shown.

|

|

|

|

Fact

limx→–2+f(x)=–∞;

limx→–2–f(x)=–∞.

Response I'll do these next two as a pair. The notation is

somewhat intricate here. We've got x→–2+ and

x→–2–. So x is getting close to –2 from the

right (+) and from the left (–). The result in both cases is

–∞. The f(x) is getting large negative as x gets close to –2.

|

|

|

|

Fact limx→+∞f(x)=–1.

Response This is new (at least in the lectures). The

x→+∞ indicates the idea that x is traveling far to the

right. As it does, f(x), the y coordinate on the graph, is getting

close to –1. I don't really know exactly what I should draw.

I drew two possible candidate graphs in magenta. Both of the pieces of curves drawn

satisfy the limit statement (there are, as I mentioned, even other

possibilities to draw). BUT we can select exactly one as a

valid candidate using other information. This piece of y=f(x) is drawn

in a region where the derivative is positive, so the graph should be

increasing. Therefore we can drop the top candidate and the other,

wiggly (?) possibilities.

|

|

|

|

Fact limx→–∞f(x)=0.

Response We've gotten to the final limit statement. Here

x→–∞ means that x is moving "far" to the left. And

the =0 tells me that the graph is getting close to the x-axis. Again

I've drawn two possible candidates. Which one will be appropriate?

Here we need knowledge once more about {in|de}creasing behavior to

make a selection. We are outside of the region where we know

f(x) is increasing, and since we had that word "only" we should expect

in this region that f(x) is decreasing. The lower alternative, the

bottom candidate, is the one we should select.

Please note that in the behavior on the right, I have drawn only the

surviving candidate as supported by the previous picture's discussion.

|

|

|

Further discussion

We've got to complete the graph. Let me move from left to right. I

know that the graph must be differentiable and therefore also

continuous. In the region to the left of –2, I think the graph

should be decreasing. I have indicated a tentative way of joining the

two pieces we've already drawn, and you should check that what's

suggested is indeed decreasing.

Now consider the region between –2 and 1. This is a bit more

complicated. We need to be increasing until 0, and then,

probably, decreasing. And we should draw a continuous graph which

connects what the limit statements gave us. So I have tried to suggest

a good candidate. Notice, please, that although I am fairly sure f has

a local maximum when x=0, I really have no idea where the local

maximum is (I don't even know if the value is positive or

negative). I've only been given qualitative information. So my

suggestion is only one of many which would be consistent with what's

required.

|

|

|

And more discussion

What happens between 1 and 4 in the picture? To the right of 3, that

is, for x>3, f should be increasing. So we guess something like the

magenta piece shown. And to the left of 3,

in the region with 1<x<3, we know that f is not

increasing, so probably (!) it should be decreasing. The result

could be what is shown in this magenta piece. but I've inserted large question

marks because something strange has happened: if we accept both

suggestions as drawn the result will certainly not be

continuous.

The graph should not have a jump in it. How can we fix this?

You need to think a bit.

|

|

|

The last piece

A curve which completes the graph validly, satisfying all of the

specifications, is shown to the right. From 1 to 3, the graph

decreases, dropping below the horizontal asymptote y=–1. Then,

at x=3, the curve begins increasing, and blends into the required

asymptotic behavior as x→+∞.

This graph has two vertical

asymptotes (x=–2 and x=1) and two horizontal asymptotes (y=0 and

y=–1).

To the right is sketched one correct answer to this problem. Again,

the problem is mostly qualitative, and there could be many specific

graphs which are correct answers to the problem. I do know that for

any solution to this problem, there will be two critical

points. There will be one at 0 which will be a local max, and there

will be one at 3 which will be a local min. Additionally, there will

be at least one inflection point, somewhere to the right of 3. (As I

mentioned in class, we could imagine the curve wiggling a bit, not

changing its {in|de}creasing behavior, so I can't declare that there

will be only one inflection point -- there will be at least

one.)

|

|

|

Comment

I began the "construction" of the previous problem by sketching a

graph and working backwards. I "read off" the limit statements from

the graph. If you just wrote limit statements at random without

starting from information that you knew was consistent, the resulting

specifications might be impossible to fulfill. Also, I really believe

I could create a function defined by an algebraic formula which had a

graph similar to what was drawn above.

Limits at +/–∞

I wanted to give examples of some of the algebraic manipulations

resulting in horizontal asysmptotes which you should know about. So

here they are.

3. What is

limx→∞[8x5–5x3+88x]/[x4+3x+9]?

In this case the degree of the top is one greater than the

degree of the bottom. Dividing the top and bottom by x4 gives

[8x–{5/x}+{88/x3}]/[1+{3/x3}+{9/x4}].

The bottom is 1+{3/x3}+{9/x4} and I think as

x→∞ the bottom gets close to 1 rather rapidly.

The top is [8x–{5/x}+{88/x3}. The second and third terms

are negligible as x gets large, and the top seems to be nearly 8x. I

think that the quotient will behave as 8x/1 for large x, and the limit

will be ∞.

A graph is shown to the right. Please notice that in this case, x goes

from 0 to 10 and y, from 0 to 80. The graph appears to resemble

closely a straight line of slope 8, which is what the algebraic

manipulation suggests.

|  |

A weird one ...

I also consider the function f(x)=(5x+7)/sqrt(x2+3). Here

let me begin by displaying a graph, since the algebraic

analysis did not proceed very well in class. Below is a graph of

y=f(x) for x between –30 and 30. Also on display (the dashed green lines) are the horizontal lines y=5 and

y=–5. Look at the graph, and observe (I hope!) that the limit as x

gets large positive of f(x) seems to be 5, and the limit as x gets

large negative of f(x) seems to be –5. The situation is more

complicated than the previous examples.

What's happening? Look at sqrt(x2+5) and "massage" it

algebraically. Well, sqrt(x2+5)=sqrt(x2·(1+{5/x2})).

| Square root facts |

|---|

The function which is sqrt

Sqrt is a function whose domain is [0,∞) and whose

range is [0,∞).

Example The value of sqrt(4) is 2. The equation x2=4

has two roots. We could indicate these two roots by writing

+/–sqrt(4), but sqrt(4) without any "decoration" always means 2. |

Multiplication works well

sqrt(A·B)=sqrt(A)·sqrt(B) if both A and B are

non-negative.

Example

sqrt(400)=sqrt(4·100)=sqrt(4)·sqrt(100)=2·10=20. |

Addition does not work with square root

There is no simple relationship between sqrt(A+B) and sqrt(A)+sqrt(B).

Example sqrt(25)=5 and sqrt(16)=4 and sqrt(9)=3. Although

16+9=25, notice that 3+4=7 which is not equal to 5.

That is: sqrt(16+9) and sqrt(16)+sqrt(9) are very different. |

Therefore sqrt(x2·(1+{5/x2})) is the same as

sqrt(x2)·sqrt(1+{5/x2}).

Please notice that if x>0, then sqrt(x2) is the same as

x. So:

If x>0 then

f(x)=(5x+7)/sqrt(x2+3)=(5x+7)/[x·sqrt(1+{5/x2})].

Divide the top and bottom by x and the result is

(5+{7/x})/[sqrt(1+{5/x2})] and I hope that now you can see

the limit as x→∞ is 5.

If x<0 then sqrt(x2) is the same as –x. You

can check this: try, say, x=–5 and see what happens. So look at

f(x):

f(x)=(5x+7)/sqrt(x2+3)=(5x+7)/[–x·sqrt(1+{5/x2})].

Dividing top and bottom by x gets

(5+{7/x})/[–sqrt(1+{5/x2})]. As

x→–∞, this becomes –5.

Damped oscillation

Damped oscillation

The function f(x)=sin(x)/x is actually something I'm more comfortable

discussing with engineering students, since things that it "models"

are easily observed. As x→∞, the bottom, x, grows, and the

top, sin(x), is caught between –1 and 1. This function should approach

0. In fact, an appropriate version of the Sandwich Theorem can

be used. By this I mean, please, just realize that:

–1/x≤sin(x)/x≤1/x.

Since both –1/x and 1/x →0 as x→∞ f(x), which is

caught in between, also approaches 0.

A graph of y=f(x) is shown to the right. The "envelope curves",

y=+/–1/x, are dashed green curves. You will

study oscillations whose amplitude go to 0 (think of a spring

vibrating in a viscous fluid).

|

A story about numbers

The sum of two non-negative numbers is 20. How

should the numbers be selected so that the product of the square of

one with the other is largest?

We should translate this problem statement into algebra, and then we

will use methods of calculus to solve the problem. This is a "toy"

problem, but the process remains valid even in much more complicated

situations. The translation is important. We may not always be able to

solve a problem, but calculus can usually move the analysis of the

problem closer to a solution.

So the two non-negative numbers will be

called x and y. We know that x≥0 and y≥0. We also know that

their sum ... is 20 so x+y=20.

We want to know How should the numbers be

selected to make something largest. What's the quantity we should try to

maximize? It is the product of the square of

one with the other and this is, I think, x2y.

The problem can be translated to the following algebraic statement:

Suppose x+y=20 and x≥0 and y≥0. Find the maximum value of

x2y.

In economics and some other disciplines, the first sentence is called

the constraint. It relates the variables of the problem and

restricts which values should be considered. It usually is related to

the appropriate domain of the problem. The second sentence is the

objective function. It describes what should be "extremized" --

in this case, what should be maximized or made largest. Here the

objective involves two variables, x and y. But the constraint tells us

that y=20–x. And therefore the problem description changes.

Suppose f(x)=x2(20–x). The domain for this problem is

[0,20]. How can we get the largest value of f?

Notice that the constraint, which shouldn't be forgotten, has

resulted in the domain statement when we write this version of the problem.

Now we can use calculus. The maximum of f on [0,20] occurs either at

endpoints or critical points.

• Endpoint evaluation

f(0)=02(20–0)=0; f(20)=(20)2(20–20)=0. I bet the

max is inside, at a c.p.

• Critical point analysis If

f(x)=x2(20–x), then f´(x)=2x(20–x)–x2. This

is 0 when =2x(20–x)–x2=0 or x(40–2x–x)=0 or x(40–3x)=0. So

we get x=0 (already checked) and x=40/3. Since

f(40/3)=(40/3)2(20–40/3) is positive (20 is 60/3),

this is where the max value of f occurs.

The answer to the question is 40/3 and 20–40/3 (we were asked

How should the numbers be selected).

Another story

A line

segment joins the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the first quadrant. A

rectangle in the first quadrant which has sides on the x- and y-axes

is inside the resulting triangle, and has a vertex on the line

segment. What is the largest area that such a rectangle can

have?

Comment

I really tried to write the specifications in this problem

carefully. After class, Mr. Orrico and

Ms. O'Sullivan convinced me that my

paragraph was not carefully written enough. I think they were

correct. Instead of the phrase "which has sides on the x- and y-axes

is inside the resulting triangle, and has a vertex on the line

segment", I had written "has sides on the x- and y-axes and a vertex

on the line segment". In that case (future lawyers should follow this

carefully!) a rectangle with vertices at (0,0), (3,0), (3,2), and

(0,2), that is a rectangle with the line segment as a diagonal, will

definitely have (I think!) all the other "eligible" rectangles inside

it. So it would definitely be the largest. This isn't what I

wanted. So my specification was not written precisely enough. I am

sorry. I believe (currently, about 5 hours later!) that what I've

written above is what I wanted and really do want. Sigh.

I will continue the discussion with the changed specification written

above.

Probably the first thing I would do when meeting a problem of this

type is to draw a picture. I think my sketch would look something like

what's to the right. Certainly, I would need the line segment joins the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the

first quadrant which is drawn. Then I likely would try to draw

a typical rectangle. Although I tried to write the specification of

the rectangle in a direct way, my desire to be brief may have made

this difficult to understand. The rectangle has sides on the x- and y-axes as shown. It

also has a vertex on the line

segment. Legitimate questions include, "What's a vertex?" and

"What line segment?" I hope, even if you've not heard the word before

or this use of the word, that you would know "vertex" means a corner

of the rectangle. And the first sentence of the problem defines "the

line segment".

Probably the first thing I would do when meeting a problem of this

type is to draw a picture. I think my sketch would look something like

what's to the right. Certainly, I would need the line segment joins the points (3,0) and (0,2) in the

first quadrant which is drawn. Then I likely would try to draw

a typical rectangle. Although I tried to write the specification of

the rectangle in a direct way, my desire to be brief may have made

this difficult to understand. The rectangle has sides on the x- and y-axes as shown. It

also has a vertex on the line

segment. Legitimate questions include, "What's a vertex?" and

"What line segment?" I hope, even if you've not heard the word before

or this use of the word, that you would know "vertex" means a corner

of the rectangle. And the first sentence of the problem defines "the

line segment".

Almost surely in my mind I would play around with the problem as

pictured, and try to see some of the eligible rectangles. The pictures

I would look at would include the two below. If the vertex were very

near (0,2), as in the left picture, I see that one side of the

rectangle would be almost 2 units long, while the other is very

small. The area of that rectangle would be small. On the other hand

(right picture), if the vertex were very near (3,0), one side of the

rectangle would be almost 3 units long, while the other is very

small. Again the area would be small. This encourages me to think

that, yes, there is a maximum and almost surely the max area will

occur for some rectangle with vertex "inside" the segment (at a

critical point of the algebraic model we will build).

| Two "extreme" rectangles |

|---|

Small area

|

Also small area

|

I will finish this problem on Thursday and discuss some additional problems.

| Thursday,

October 29 | (Lecture #17) |

|---|

What first derivatives can tell you

We learned last time:

- If f´>0 on an interval, f is increasing

on that interval. Therefore if you "move" from left to right on the

graph, you'll also move up.

- If f´<0 on an interval, f is decreasing

on that interval. Now if you "move" from left to right on the

graph, you'll move down.

What second derivatives can tell you

The sign of the second derivative on an interval also has some neat

geometric information. Here is the logic:

If f´´>0 on an interval then f´ is increasing

on that interval. So moving from left to right means that the slope of

the tangent line increases. I don't know enough about animations to

put my walking demonstration of this on the web (I wish I did, but I

am lazy), but to the right is a static picture of what I am trying to

describe. This curve is concave up.

Of course, if f´´<0 on an interval then f´ is

decreasing on that interval. So moving from left to right means

that the slope of the tangent line decreases. A typical geometric

picture of this situation is to the right. (Since I am lazy, all I did

was flip the previous picture -- drawing programs are wonderful.)

This curve is concave down.

Of course, if f´´<0 on an interval then f´ is

decreasing on that interval. So moving from left to right means

that the slope of the tangent line decreases. A typical geometric

picture of this situation is to the right. (Since I am lazy, all I did

was flip the previous picture -- drawing programs are wonderful.)

This curve is concave down.

The Second Derivative Zoo

Before we went on, I thought giving several (relatively) simple

examples would be useful. I learn far more from examples than from

definitions, and even from theorems. So here is my "zoo" or collection

of concavity examples.

| Examples and discussion | Graphs |

|---|

| x3

Here f(x)=x3 so f´(x)=3x2. Away from x=0,

this is certainly positive, so f is increasing in (–∞,0] and in

[0,∞). Actually, if we "glue" the intervals together, we can

see that f is increasing in all of the real numbers.

Since f´´(x)=6x, I know that f is concave up where

6x>0: this is (0,∞). Similarly, f is concave down

where 6x<0. This is (–∞,0).

At 0, the x-axis (equation:y=0) is a horizontal tangent line. Also at

x=0, the concavity changes from down to up. This is called an

inflection point.

|  |

| x1/3

Well, this function is a bit weirder. Here

f´(x)=(1/3)x–2/3. You need to think about this for a

moment. The derivative is a negative power of x. This means

that the domain of the derivative does not include 0 (we don't divide

by 0!). Geometrically, this function is the flip over the "main

diagonal" y=x of y=x3: it is the inverse of

x1/3. The previous horizontal tangent line becomes a

vertical line, which has no slope. Since

=(1/3)x–2/3=(1/3)(1/x2)1/3, I know that the derivative (where it

exists!) is always positive. This function is increasing always.

Since f´(x)=(1/3)x–2/3, we know that

f´´(x)=–(4/9)x–5/3. Again, the domain is non-zero

x's. But what is the sign of f´´(x) for those non-zero x's?

Here please notice that 5 and 3 are both odd. This is important. A

negative number raised to an odd integer power or an odd integer root

is negative. But look closely: in front of the formula, before the

(4/9) is –: a minus sign. So f´´ is positive

when x is negative, and therefore the graph is concave up for

negative x. For similar reasons, the graph is concave down when x is

positive. And x=0 is a point on the graph where concavity changes, and

therefore is an inflection point.

|  |

| 1/x

There is a tricky bit of language here, which I will mention

later. Since f(x)=1/x=x–1, I know the

f´(x)=–1/x2. Squares are always positive, so this

derivative is always negative, and therefore, inside each interval

in which this function is defined, the function is decreasing.

This means f is decreasing inside (–∞,0) and f is decreasing

inside (0,∞). Notice, though, that f(1)=1 and f(01)=–1. Even

though –1<1, we have f(–1)<f(1): f is not decreasing "across"

the intervals.

If we compute correctly, f´´(x)=2/x3. 3 is an

odd power, so the graph is concave down in (–∞,0) and concave

up in (0,∞). The domain of f does not include 0, so

there is no point of inflection!

|

|

|

|x|

I put this in to stimulate some conversation. If you are clever and

just look at the graph, you can "read" the derivative. The function

f(x)=|x| is differentiable except for x=0. When x<0, f´(x)=–1,

and when x>0, f´(x)=1. Actually, the second derivative also

"exists" when x is not 0: f´´(x)=0 for all x not equal to

0. The graph has no concavity as it is usually understood.

|  |

| x4

If f(x)=x4, then f´(x)=4x3 and

f´´(x)=12x2. If x is not equal to 0, then

the second derivative is positive. The graph is concave up. Notice

that although f´´(0)=0, this graph has no point of

inflection! The concavity on both sides of x=0 is "up": the graph is

concave up in both (–∞,0) and (0,∞). Since concavity

is the same on both sides of 0, the origin is not a point of

inflection.

Comment

Comment

People will say that y=x4 "is" or "looks

like" a parabola. Well, right here (to the right, here!) are graphs of

y=x2 and y=x4. I will agree that the graphs

resemble each other in many ways. They are both concave up always, go

through (0,0), and are symmetric with respect to the y-axis. But

please look a bit more closely. y=x4

is flatter near the origin (higher powers of small numbers are

smaller!). As soon as the x's get out of [–1,1], that curve grows much

larger than y=x2 (higher powers of

large numbers are larger). The parabola is y=x2 and it has

some interesting geometric and physical properties (for example,

mirrors are made to have parabolic cross-section to help aim light

beams and telescopes) which are not shared by y=x4.

|

|

Inflection point

x is an inflection point of f if

- x is in the domain of f.

- The concavity of the graph of f on the two sides of x (less than

and greater than) is different.

Templates (pieces of curves) based on signs of f´ and

f´´

The QotD was to fill in curves in the four spaces in the table below

this paragraph. Each space was supposed to be a small segment of a

curve which characteristically looked like the properties which define

its place in the table: So {in|de}creasing and concave {up|down} are

these properties and most students seemed to fill in the blanks

correctly. The little chunks (?) of these curves can be used to

"build" more complicated curves.

The Gaussian (bell-shaped) curve

The Gaussian (bell-shaped) curve

I wanted to graph a "random" (not!) curve defined by a formula. What

we looked at was f(x)= e(–x2). This turns out to

be a rather important function in analyzing experimental

results. Any "real" repeatable experiment with a measurable

outcome is likely to have the numbers scattered so they resemble

this bell-shaped curve. This phenomenon is not obvious at all!!

The exponential function's outputs are never negative and never

0. Therefore no part of the graph will be on or below the

x-axis. Since –x2 is always less than or equal to 0, and

these numbers serve as inputs to exp, I bet that the outputs from exp

will be less than or equal to 1, and will be equal to 1 only at

x=0. Also this graph is even, symmetric with respect to the x-axis,

since (–x)2=x2. I hope this explains to you why

the graph looks the way it does. But let me try analyzing the graph

using the first and second derivative.

If f(x)=e–x2 then

f´(x)=(e–x2)(–2x). The exponential function is

very nice. It is never 0 and always positive. Therefore the

only x for which f´(x)=0 is when –2x=0. So x=0 is the only

critical number. Now reasoning using the Intermediate Value Theorem

says that f (which is certainly continuous!) can have only one sign

for x<0 and one sign for x>0 (or else f(x) would have to have to

be 0 again). We can check signs at, say, x=1 (where the derivative is

negative) and x=–1 (where the derivative is positive). f is increasing

in (–∞,0) and f is decreasing in (0,∞). Naturally 0

represents a local (and indeed, absolute!) maximum.

What information can we get from the second derivative? If we use the

product and the chain rule correctly, then

f´´(x)=(e–x2)(4x2–2). Logic

similar to the preceding asserts that this is 0 exactly when the

non-exponential factor is 0. But 4x2–2=0 when

x={+|–}1/sqrt(2). Again, we can check signs in between the 0's of f'',

and f will be concave up for x<–1/sqrt(2) and for

x>1/sqrt(2). For x between –1/sqrt(2) and +1/sqrt(2), the graph

will be concave down. The points where x={+|–}1/sqrt(2) are where the

concavity of f changes: these are called inflection

points. These particular inflection points are related to the

standard deviation, which represents dispersal from an average when

this function is used in statistics. The center of the curve, at x=0,

is related to the mean of the data observed.

The diagram/picture above is an attempt to indicate how a person could

assemble the information about signs of the first and second

derivative, and patch together template pieces. The patched-together

curve should be continuous (no breaks) and differentiable

(smooth). This all takes some practice!

Graphing x3(x–1)4

Graphing x3(x–1)4

Here I invited students again to use a graphing calculator and try to

see what y=x3(x–1)4 "looked like". I did remark

that the "action" took place somewhere between –1 and 2. The result of

this was something like the graph shown to the right. I believe that

calculators and graphing devices are wonderful, but sometimes they

almost conceal what's going on.

Here f(x)=x3(x–1)4. If we want to find out where

f is increasing and decreasing, we really should look at

f´(x). For this we need the product rule and the chain rule. So:

f´(x)=3x2(x–1)4+x34(x–1)3.

Generally I am against "simplifying" because I view it as mostly a

chance to make lots of mistakes. But here some simplifying will reveal

structure in the derivative. So please notice the common factors, and

what you get is as follows:

f´(x)=x2(x–1)3(3(x–1)+4x)=x2(x–1)3(7x–3).

What can we tell about where the derivative is 0 and where it is

positive and where it is negative? Well, the different factors allow

us to deduce that the derivative is 0 at x=0 and x=1 and x=3/7.

If x is very large positive, say, then f(x) is a product of three

factors, all of which are positive. And if x is very large negative,

then the x2 is positive and the (x–1)3 is

negative and the 7x–3 is negative. Therefore f(x) in that range is

positive also. So we have learned (using logic from the Intermediate

Value Theorem as before) that the derivative is positive on at least

the intervals (–∞,0) and (1,∞). There is a chance

for the derivative to change signs at x=0, but the factor which

controls sign change there is x2: since 2 is even, there is

no sign change at x=0. But there is a sign change at x=3/7 and at

x=1. So now we have broken up the real line into pieces based on

the signs of the derivative of f:

Deriv is + Still + Now it is – Back to + here

<---------------0-----------3/7--------------------1------------------->

Func increases increases The func decreases Here it decreases

|

So from this I learn that f has critical points at 0 and 3/7 and 1. We

can also learn that f has a local max at 3/7 and a local min at

1. This is not entirely clear from the initial graph. Actually,

if we just look at the graph from –.1 to 1.1, you can see some of the

structure. This is shown to the right. Please notice that the vertical

scale of this graph is very small. This might all be difficult to see

without looking at the calculus first.

|

|

Let's consider the concavity of this function, and make some

guesses about the number and location of inflection points. We can be

sure about this if we find the second derivative.

I will use the product rule, and make the second factor, a product

itself. So:

f´(x)=x2(x–1)3(7x–3)=

x2((x–1)3(7x–3))

f´´(x)=2x((x–1)3(7x–3))+x2(3(x–1)2(7x–3)+(x–1)3(7))

So let me try to "simplify" f´´(x). We will get:

x(x–1)2(2(x–1)(7x–3)+3x(7x–3)+x(x–1)7)=

x(x–1)2(2(7x2–10x+3)+21x2–9x+7x2–7x)=x(x–1)2(42x2–36x+6)

So the second derivative is 0 at x=0 and at x=1 and at the roots of

42x2–36x+6=0: those are x=(3/7)+/–sqrt(2)/7 (approximately

.227 and .631). The second derivative does not change sign at 1

because the factor is (x–1)2, an even power. It does

change sign at 0 and the two other numbers which are on either side of

the local max. There are three inflection points.

I needed to work fairly hard to get everything correct in the preceding

example.

Second Derivative Test

There is a result which allows you to tell when a critical point is a

local max or local min if you have information about the second

derivative at that point. It goes like this:

|

If f´(x)=0, and if f´´(x)>0,

then f has a local min at x. Example –x2 at 0.

| |

If f´(x)=0, and if f´´(x)>0,

then f has a local min at x. Example x2 at 0.

| |

If f´(x)=0, and if f´´(x)=0,

then nothing can be deduced. Example –x4,

x4, and x3 at 0.

|

I don't often use this result, because I am lazy and computing the

second derivative (and evaluating it!) may be work. Usually I can

examine the first derivative, if needed.

Inflection points as you drive!

Suppose you are driving along a road, which happens to be the graph of

a function. Please refer to the picture to the right. This discussion

is an effort to persuade you that inflection "occurs" in the "real

world". My car is the weird object shown at the lower left, and it is

moving in the direction of the red arrow. This is a one-way road and I

won't hit anything (I hope).

Suppose you are driving along a road, which happens to be the graph of

a function. Please refer to the picture to the right. This discussion

is an effort to persuade you that inflection "occurs" in the "real

world". My car is the weird object shown at the lower left, and it is

moving in the direction of the red arrow. This is a one-way road and I

won't hit anything (I hope).

As I drive along the road, I steer to the left (that's the A region of

the road). Eventually I come to a place where the road begins to

bend the other way, at B. After that point, in the C region, I

steer right. The bending place, where the switch from left steering to

right steering occurs, is an inflection point.

Please notice that from the point of view of the car, it actually

doesn't matter (no gravity, we are looking from above) whether the

curve is decreasing or increasing. The steering occurs as a response

to how the curve is bending. When the bending changes (inflection!) we

must change steering direction -- if we want to stay on the road,

anyway.

What could have been the QotD

To the right is shown a graph of the derivative of

f(x). The function is intended to have domain all of R, the

real numbers, and the arrows at the end of the graph are intended to

indicate that the graph goes on forever behaving nicely. Please answer

the questions in A first, and then draw the graph requested in B.

To the right is shown a graph of the derivative of

f(x). The function is intended to have domain all of R, the

real numbers, and the arrows at the end of the graph are intended to

indicate that the graph goes on forever behaving nicely. Please answer

the questions in A first, and then draw the graph requested in B.

A. Use this graph to answer the following questions as well as you

can.

- What are the critical points of f?

- In what intervals is f decreasing?

- In what intervals is f increasing?

- For each critical point: is it a local max or a local min or

neither?

- Where is the graph of f concave up?

- Where is the graph of f concave down?

- Where are the inflection points of f?

B. Sketch a graph of y=f(x) using the information just

described.

There will be many different valid graphs, but they will all share the

same qualitative features.

Please try to write a solution on your own. Then you may wish to look

at a solution I wrote.. Do this yourself

first, please. This is a valid exam question, and you should

check your own ability with such material.

|

| Tuesday,

October 27 | (Lecture #16) |

|---|

Two "easy" exercises

Two eager volunteers, Mr. Kadriu and Mr. Thistle, did the first problem

below. At the same time, eager volunteers Mr. Patel and Mr. Montero

did the second problem.

- Problem 53 of section 4.2 Find the max and min values of

f(x)=(ln(x))/x on the interval [1,3].

Endpoints f(1)=ln(1)/1=0 and f(3)=ln(3)/3.

The derivative

f´(x)=[(1/x)(x)–1·ln(x)]/x2. The top is

1–ln(x), and this is 0 when ln(x)=1, so x=e.

Plugging in f(e)=ln(e)/e=1/e.

Biggest/smallest of the available candidates Max must be 1/e and min

must be 0.

Comment We needed to compute 1/e: its decimal expansion begins

.3678, and ln(3)/3: its decimal expansion begins .3662. I certainly

can't "see" which number is larger. And, really the graph hardly

helps. (Later in this lecture we'll see another way to detect the

highest point without extensive computation.)

- Problem 54 of section 4.2 Find the max and min values of

f(x)=3ex–e2x on the interval [–1/2,1].

Endpoints f(–1/2)=3e–1/2–e–1 and

f(1)=3e–e2.

The derivative f´(x)=3ex–2e2x. When

is this 0? Well, we can factor:

ex(3–2ex)=0. Since ex is never 0,

this is 0 when 3–2ex=0 so ex=3/2 and x=ln(3/2).

Plugging in

f(ln(3/2))=3eln(3/2)–e2ln(3/2)=3(3/2)–(9/4)=9/4.

Biggest/smallest of the available candidates Max must be 9/4 and min

must be 3e–e2.

Comment Again, you can compute to compare the three values, or,

in this case, maybe the comparison can be done by "pure thought". So,

for example, f(1)=3e–e2=(3–e)e is about .3(2.7),

approximately .8 And f(1/2)=3e–1/2–e–1 is about

3/2–1/3, which is 7/6. And the other value is 9/4. So the 9/4 is

largest, and the (approximately) .8 is smallest.

What should you learn?

I do not think that that finding the max or min of even these rather

simple "toy" examples is totally straightforward. I don't think that

the answers can be guessed, even for these examples. And just trying

numbers at random is quite wasteful and would qualify as a stupid

strategy. The method outlined really works!

Rolle's Theorem

If f is continuous on[a,b], and if f(a)=0 and f(b)=0, and if f is

differentiable inside the interval, then there is at least one number

c inside the interval where f´(c)=0.

If f is continuous on[a,b], and if f(a)=0 and f(b)=0, and if f is

differentiable inside the interval, then there is at least one number

c inside the interval where f´(c)=0.

To the right is a typical picture of the situation described in

Rolle's Theorem. Since the function is glued down (?) on the x-axis at

a and b, either the function is always 0 (so there are lots of c's) or

the absolute max and absolute min occur inside the interval. There may

be more than one of each. Since the function is differentiable, these

max's and min's occur at critical points where the derivative is 0, as

shown.

Below is a gallery of possible "Rolle" situations. The first, to the

left, is the simplest and silliest. The function is 0 in the whole

interval. Then any c is a valid candidate for the consequence of the

theorem. The second picture shows what happens if f is positive

somewhere. Then the absolute max must occur inside, and it must occur

at a local max inside the interval, and since f is differentiable,

f´(c)=0 there. The next is the negative situation, and the last

picture is what might happen if there f had a mixed sign behavior.

Rolle's Theorem tilted

Rolle's Theorem seems very specialized. What would happen if we tilted it?

That is, we took the coordinate axes and rotated the whole picture?

Then the graph is no longer glued down at the endpoints. This is the

important generalization that people use constantly. Of course, the

picture is relabeled and everything is more conventionally drawn.

Here is one of the two results in this course that anyone who

uses calculus will think about quite frequently.

The Mean Value Theorem (MVT)

Suppose f is differentiable in [a,b]. Then there is at least one c

inside the interval so that f´(c)=(f(b)–f(a))/(b–a).

Suppose f is differentiable in [a,b]. Then there is at least one c

inside the interval so that f´(c)=(f(b)–f(a))/(b–a).

Discussion To the right is a tilted and relabeled picture. The

line segment joining (a,f(a)) and (b,f(b)) has slope equal to

(f(b)–f(a))/(b–a). The other indicated line segments are pieces of

tangent lines which are parallel to the segment joining (a,f(a)) and

(b,f(b)). Since they are parallel, their slopes must be equal. But the

slope of a tangent line at c is f´(c), and that's the equation

which appears above.

If you want an algebraic verification of MVT, then look at the end of

section 4.2. This picture is sufficient for my purposes. I want to

show you some of the ways people use this result.

Simple (?) observation #1

Suppose f is differentiable, and in some interval I we know for some

reason that f´ is always 0. What happens? Well, take two

points, x1 and x2 in I with

x1<x2. MVT says that

(f(x2)–f(x1))/(x2–x1)=f´(c)

But the right-hand side of the equation is 0. So the quotient on the

left-hand side must then have 0 on top:

f(x2)–f(x1)=0, which means

f(x2)=f(x1) for any choices of x1 and

x2. This means that f is constant.

If f´=0 always, then f is

constant.

Physical meaning

Well, one way to get a physical (?) interpretation of this statement

is to imagine that f(x) is the position depending on time, x. (Sorry:

you could rotate the x and get a t, if that makes you happier.) So

f(x) reports the position on a line. Then the statement above

translates to:

If velocity is always

zero, then position is constant.

Well, it sure doesn't look profound, but maybe it does make sense. By

the way, this "simple" deduction which is so clear physically wasn't

verified mathematically for about 150 years. Stupid human beings. (!)

(?) Or maybe this stuff is somewhat subtle?

Simple (?) observation #2

Suppose f is differentiable, and in some interval I we know for some

reason that f´ is always positive. What happens? Well, take two

points, x1 and x2 in I with

x1<x2. MVT says that

(f(x2)–f(x1))/(x2–x1)=f´(c)

Now let's see: the right-hand side is now supposed to be positive. The

bottom of the left-hand side is positive (since

x1<x2 means

x2–x1>0). So we have a fraction with a

positive bottom equal to a positive number. So the top of the fraction

should be positive. That means f(x2)–f(x1)>0

so that f(x1)<f(x2). So what do we know:

IF f´ is positive, THEN x1<x2

implies f(x1)<f(x2).

Physical meaning

Well, if derivative corresponds to velocity, and position corresponds

to the original function (with higher corresponding to more

right position on the line), then:

If velocity is always

positive, then position is moving steadily right.

If velocity is always

positive, then position is moving steadily right.

Another way of thinking about this is graphical. If you wish, you

could imagine position as a function of time. Then the "progress" of

time might be the horizontal axis, and position in this diagram would

be the vertical axis. Position getting bigger would mean that the

graph of position versus time would be getting higher. So a

qualitative picture of this sort of graph is shown to the right.

Simple (?) observation #3

I will reverse the sign of the derivative. So here suppose f is

differentiable, and in some interval I we know for some reason that

f´ is always negative. What happens here? Well, take two

points, x1 and x2 in I with

x1<x2. MVT says that

(f(x2)–f(x1))/(x2–x1)=f´(c)

Now let's see: the right-hand side is now supposed to be negative. The

bottom of the left-hand side is positive (since

x1<x2 means

x2–x1>0). So we have a fraction with a

positive bottom equal to a negative number. So the top of the fraction

should be negative. That means f(x2)–f(x1)<0

so that f(x1)>f(x2). So what do we know:

IF f´ is negative,

THEN x1<x2 implies

f(x1)>f(x2).

Physical meaning

Again, derivative corresponds to velocity, and position corresponds to

the original function (and higher still means position is more to the

right, and lower position means more to the left on the line),

then:

Again, derivative corresponds to velocity, and position corresponds to

the original function (and higher still means position is more to the

right, and lower position means more to the left on the line),

then:

If velocity is always

negative, then position is moving steadily leftt.

Again, we could think graphically. Position is a function of

time, the "progress" of time is the horizontal axis, and

position is the vertical axis. Position getting

smaller would mean that the graph of position versus time would be

getting lower. A qualitative picture of this sort of grpah is

shown to the right.

Further definitions

A function f is increasing on an interval I if whenever we take

x1 and x2 in I with

x1<x2, then

f(x1)<f(x2).

A function f is increasing on an interval I if whenever we take

x1 and x2 in I with

x1<x2, then

f(x1)<f(x2).

Facts

MVT implies:

If f´ is positive on an interval, then f

is increasing on that interval.

If f´ is negative on an interval, then f

is decreasing on that interval.

What we can say with graphical (qualitative) evidence

What we can say with graphical (qualitative) evidence

This is basically a discussion of problem 24 in section 4.3. The

problem gives a graph of the derivative f´(x) of

a function f(x). Please let me repeat: the graph is the

derivative of the function. I've attempted to copy the graph in the

picture to the right.

First, we are asked to "find the critical points of f". Since f is

differentiable (otherwise we wouldn't be looked at a graph of f´,

darn it!) the critical points here are where f´(x)=0. Look at the

graph. The curve crosses the x-axis at three values of x: –1, 0.5, and

2. These are the critical points of f.

Then we are asked to determine whether these critical points are local

max or local min or neither. So let me think through this with you.

|

Local analysis near x=0.5

Look closely at the graph of f´ in a small interval to the left

of x=0.5. The graph (inside the very light blue region) is above the

x-axis. So in this interval, the derivative is positive and

therefore the function is increasing. Look now at the graph of

f´: in a small interval to the right of x=0.5. The graph (inside

the very light green region) is below the x-axis. So in this interval,

the derivative is negative and the function is

decreasing.

|  |

What should the graph of f (not the derivative!) look like? To

the left of 0.5, the function is increasing. The derivative at 0.5 is

0, so the tangent line is horizontal. To the right of 0.5, the

function is decreasing. Surely f has a local maximum at 0.5. I can't

tell the value of f(0.5), but I can tell you that value is

larger than f(x) for nearby x's, on either side of 0.5

f has a local maximum at 0.5.

|

|

|

Local analysis near x=2

The situation is similar but reversed near x=2.

A "blow up" of the graph of f´ near x=2 is shown to the right.

In a small interval to the left of x=2, the graph of the derivative

(inside the very light blue region) is below the x-axis. So in this

interval, the derivative is negative and therefore the function

is decreasing. The graph of f´: in a small

interval to the right of x=2 is inside the very light green

region, above the x-axis. So in this interval, the derivative is

positive and the function is

increasing.

|  |

What should the graph of f (again, the graph of f, not of its

derivative!) look like? To the left of 2, the function is

decreasing. The derivative at 2 is 0, so the tangent line is

horizontal. To the right of 2, the function is increasing. Surely f

has a local maximum at 2. Again, we don't know the actual value of

f(2), but we do know its relative value. f(2) is

smaller than f(x) for nearby x's, on either side of 2.

f has a local minimum at 2.

|

|

|

Local analysis near x=–1

I saved the most interesting (or maybe most irritating!) for

last. What do we see when we look very closely at the derivative near

x=–1? Well, to the left of –1 the derivative is positive,

above the x-axis, so the function itself should be increasing

in that interval. And to

the right of –1, the derivative is also positive, so the

function is also increasing there. That's what the graph of the

derivative of f declares.

|  |

The graph of f will show some delicate (?) behavior near –1. In a

small interval to the left of –1, we know f should be increasing (as

we walk from left to right, the graph will go up). And the same sort

of qualitative behavior will be true for the graph of f in a small

interval to the right of –1: up again. In fact, the graph is just

going up, increasing in the whole interval. The most fascinating (?)

aspect is that since f´(–1)=0, we'd better draw the graph of f so

that it has

a horizontal tangent line at –1. And that's what I've tried to show to

the right. If you are not used to this sort of kink in a graph, take a

look.

f has neither a local minimum nor a local maximum at

x=–1.

|

|

| |

An office hour question

Mr. Orrico asked me in my office before

class about problem 28 of section 4.3. Here y=x(x+1)3 and

you are asked to find the critical points and find intervals in which

the function is increasing and decreasing. He found y&3180; and found

that it was equal to 0 at exactly two values of x, –1 and

–1/4. So the derivative is not zero in the interval

(–∞,–1) and in the interval (–1,–1/4) and in the interval

(–1/4,∞).

How many SIGNS can the derivative have in the interval (–1/4,∞)?

Well, I think the derivative, which is a polynomial, is continuous. If

it is both positive and negative in that interval then the

Intermediate Value Theorem tells me that the derivative must be 0

inside the interval. But it is not zero. Therefore the

derivative can have only one sign inside (–1/4,∞). Similar logic

tells me the derivative can have only one sign in the the interval

(–1,–1/4) and only one sign in the interval (–∞,–1). I don't

know what the signs are, but I do know that the sign doesn't

change. How can I discover what the sign is in the interval

(–1/4,∞)? I can check one value of f´ inside that